What is a manifestos?

Simply put, a manifesto is a statement of ideals and intentions. One of the most famous examples is The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (the word is right there in the name!), but there are many others. The Declaration of Independence is a manifesto. So is Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream Speech.”

According to The Art of Manliness (a site that we promise can be enjoyed by ladies, too), “A manifesto functions as both a statement of principles and a bold, sometimes rebellious, call to action. By causing people to evaluate the gap between those principles and their current reality, the manifesto challenges assumptions, fosters commitment, and provokes change.”

Because of their power to provoke change, manifestos are often embraced by creative and political types, but you don’t have to be a writer, artist, or revolutionary to draw up your own personal manifesto. Here’s how to write your own in five steps:

1. Get Inspired.

Read what others have written. Check out this list of ten great modern manifestos to get you started, but don’t feel that you have to conform to any of these examples. This is your personal manifesto, so copying someone else kind of defeats the purpose.

2. Make Notes.

Your manifesto has three basic components: beliefs, goals, and wisdom. Grab a notebook and write “I believe…” at the top of a blank page, then think of five or ten ways to complete the statement. On the next page, write “I want to…” and fill in the blanks with ways that you’d change the world. Finally, write “I know this to be true…” and record words of wisdom. These can be things you’ve learned from your own experience, wisdom passed down from your family, or even inspirational quotes.

3. Write a Rough Draft.

Using the notes you made, create a rough draft of your manifesto. It can be as long or as short as it needs to be. You can write in long, flowing paragraphs, or you can make a bulleted list like architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s manifesto for his apprentices. You could even create an infographic-style manifesto if you’re a visually inclined person. Don’t worry about impressing your significant other, your parents, your best friend, or the fourth grade teacher who criticized your penmanship.

4. Put It Away, Then Proofread.

Once you’ve written the draft version, set it aside for a day or two. Resist the urge to tinker with it! When you come back to it with fresh eyes, you may find that some of the statements don’t ring quite true. Cut out any instances of the word “try”: As Yoda told Luke in The Empire Strikes Back, “Do or do not. There is no try.” While you’re rereading, you’ll probably also find some typos. If proofreading isn’t your forte, try using an automated proofreader.

5. Live It.

A personal manifesto is a declaration of your core values. It’s like a mission statement and owner’s manual for your life, so don’t let it sit in a drawer or a file you never open on your computer. Hang it over your workspace, put it on the fridge, make it your desktop background, or print it on a laminated card you keep in your wallet: the idea is to read your manifesto regularly to reaffirm those values and remind you of your goals.

Keep in mind that your priorities and goals will change over time. Like the U.S. Constitution, your manifesto is a living document. Let it grow along with you as you go forth to follow your dreams!

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/write-manifesto_b_5575496?guccounter=1

What makes a good manifesto?

1. Manifestos usually include a list of numbered tenets.

The format has been de rigeur since at least as far back as The Declaration of the Rights of Man (1789). It conveys a sense of urgency and straight talk. This is also why manifestos feel so contemporary: their close resemblance to click-bait top 10 lists.

2. Manifestos exist to challenge and provoke.

Any manifesto worth reading demands the impossible. Surely the best first line since Marx and Engels’s The Communist Manifesto (1848) is the breathless opener to Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto (1967), which reads: “Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex.” It is dangerous and unpredictable, like the “thrill-seeking females” it imagines as its foot soldiers, and is nothing if not ambitious.

3. Manifestos are advertisements.

The Futurist Marinetti made this especially true, embracing and pioneering new techniques for advertising (one of Benjamin’s “shocks” of modernity) to promote his international movement. Since Futurism, the manifesto has come into its own as something that advertises mainly itself. But it also, in most cases at least, advertises an “ism.”

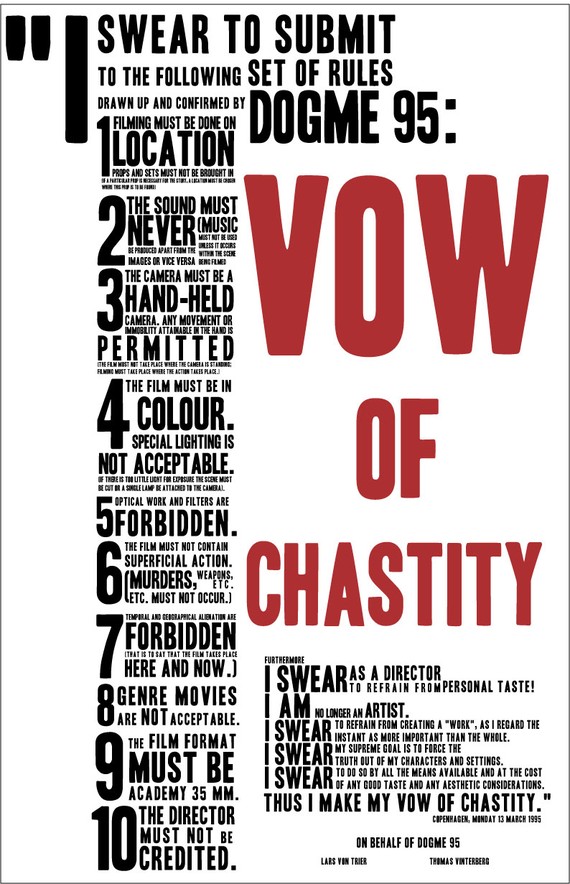

Marinetti’s favorite lesson from advertising was the old adage “there’s no such thing as bad press.” He wrote about “The Pleasure of Being Booed” and picked fights with audiences across Europe. Soon other isms followed his lead, using shock and outrage as their chief mode. The Vorticist Wyndham Lewis described it as a game played by artists with the press and public before the rude intrusion of the First World War. It has been a popular technique ever since: the film director Lars von Trier, for example, who contributed to the genre with his “Dogme 95” manifesto, has in recent years elevated bad press to an art form.

4. Manifestos come in many forms.

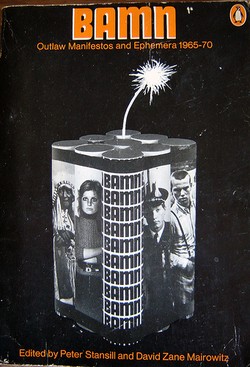

During the “second-wave” avant-garde of the 1960s, the manifesto experienced a major rebirth, becoming again part of the general atmosphere as it was in Europe before and after the First World War. One anthology, BAMN (By Any Means Necessary): Outlaw Manifestos and Ephemera, 1965-70 (1971), described some of the situations in which the manifesto might have appeared and the forms it might have taken:

perhaps it caught your eye as a flyposter, nailed to a tree, published in a “now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t” magazine or news-sheet. It could have been incanted at a wedding service, passed round as trading cards, posted as a chain letter, read on a menu. It may even have whizzed past your head while wrapped round a brick.

The BAMN anthology provides some good examples from the heady late-’60s, including the “Outlaws of Amerika” trading card series. Created for the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the cards depict various members of the Black Panthers and “200,000 pot smokers” (a figure that sounds charmingly conservative today). Also from 1968 is a manifesto reportedly written by Salvador Dali and found “behind the barricades in Paris” —perhaps even wrapped around a brick and ready to be tossed at The Establishment.

Today the manifesto is experiencing a rebirth of a very different kind. With the proliferation of the Internet in the past decade, the manifesto has expanded into every corner of the arts (and crafts), as well as academia (e.g. “The Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0”). But the most startling change is that the manifesto, which has long borrowed from advertising, has itself been coopted as a business-friendly genre. It has of late become tame, even cute: an untroubling, unironic, fully digested meme for the attention deficient.

The new wave of “inspirational” self-help manifestos—as if the vast majority of manifestos weren’t inspirational—demonstrates the malleability of the form. The recent boom shows no sign of ending. As one new guru of positivity and self-promotion, Alexandra Franzen, recently proclaimed: “It doesn’t matter if you’re a stay-at-home mama, a rising entrepreneur, an aspiring author, a CEO, or a preschool teacher—everyone needs a blow-your-mind manifesto. It’s just . . . necessary. And sexy.”

5. Manifestos are better very short than very long.

The longer a manifesto is, the exponentially crazier and duller it seems to get. If a manifesto is a type of advertisement, then ask yourself: Who would write a 35,000-word advertisement? The Unabomber, for one. Ted Kaczynski’s “Industrial Society and Its Future” (1995) is a classic of the extreme end of the genre. A too-long manifesto is, at the very least, something akin to an eight-hour speech by Fidel Castro. It is a marathon performance intended to impress by sheer excess. If you still need convincing, take a look at the endless cut-and-paste drivel of Norwegian mass murderer Anders Breivik’s “2083: A European Declaration of Independence” (2011) or, indeed, Adolf Hitler’s 700-page Mein Kampf (1925). These are not the examples most of us want to follow.

Better, obviously, is something like this: “A Short Manifesto” (1964) by the Dutch conceptual artist Stanley Brouwn. It ends with a vision of the future, in 4,000 AD:

NO MUSIC

NO THEATRE

NO ART

NO

THERE WILL BE SOUND

COLOR

LIGHT

SPACE

TIME

MOVEMENT

Or the “Laws of Sculptors” (1969), by the English artists Gilbert & George, written during the same decade of social upheaval but with a tone that rejected the surrounding chaos. In their manifesto, four concise, keep-calm-and-carry-on-style “laws” are laid out for fellow artists: “Always be smartly-dressed, well groomed relaxed and friendly polite and in complete control.”

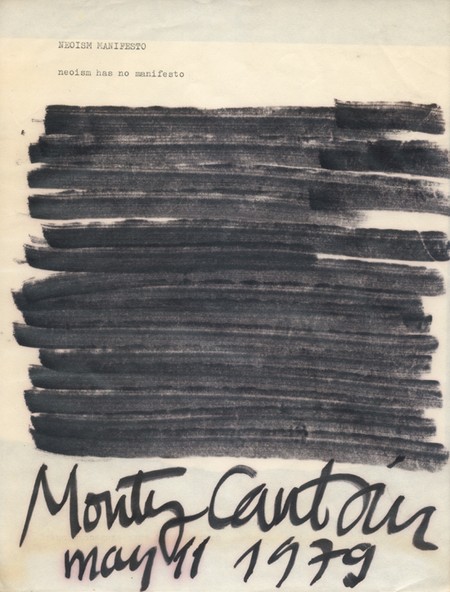

6. Manifestos are theatrical.

When I first encountered the manifesto as an undergraduate I was lucky enough to see it as a living thing and not a thing of the past. This was thanks to my professor, a charismatic Romanian woman in her 40s who also happened to be a Neoist performance artist and manifesto writer—a real-life avant-garde provocateuse. The summer course she taught traced the radical avant-garde that descended from Futurism through Vorticism, Dada and Surrealism to Situationism and post-punk movements like Neoism.

In our daily meetings she revealed a degree of permissiveness that we had not heretofore encountered, even in our most liberal research seminars. One student, a theater major named Peter, declaimed his manifesto in the nude, which was uncomfortable given the restrictive confines of our basement classroom. He had scrawled the main tenets of his manifesto in Sharpie across his chest and limbs. He even wrote something down there, though none of us got close enough to read what it said. When Peter finished, our professor complimented him on his “excellent provocation” and his “Olympian” physique. He got an A.

Performance is part of the manifesto’s materiality, its existence in the world. Marinetti made art into a kind of Punch and Judy show, full of pantomime fisticuffs and bold, simple story lines: Destroy the past, embrace the future. From Dada manifestos in the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916 to the radical street theater of the 1960s to Lars von Trier’s scattering of red leaflets printed with his “Vow of Chastity” into the audience at a Paris cinema conference on the future of film in 1995, the manifesto—manu festus, “struck by hand”—has always been about striking gestures.

7. Manifestos are fiction dressed as fact.

Particularly in the preamble, manifestos are a kind of storytelling. The two most famous manifesto templates, The Communist Manifesto and “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism,” begin as stories. The first opens with a ghost story (“A specter is haunting Europe”), the second is a tale of how the manifesto was written (“blackening reams of paper with our frenzied scribbling”) and how the movement was founded. The engaging origin narrative of Futurism includes a car chase (in 1909!) that ends with Marinetti crashing into a ditch and being hauled out by a group of fishermen. From that very spot, “faces smeared with factory muck,” their incendiary manifesto was proclaimed to Italy and the world.

8. Manifestos embrace paradox.

Fleeting and permanent, serious and ridiculous, sincere and ironic, always undermining their own authority, manifestos are unstable texts in the extreme. The bluster and bravado of any Futurist manifesto is at once self-parody and serious polemic. Its roots are traceable to influences like Nietzsche, Sorel, and Whitman, but also to the paradoxes of late-Victorian dandies and aesthetes like James McNeill Whistler and Oscar Wilde. Wilde, so fabulously flippant and ironic in his art, gravely pursued his aesthetic and moral beliefs to his death.

9. Manifestos are always on the bleeding edge.

Make it new: In our age of ever-shortening texts, this dictum of Ezra Pound remains likely the shortest manifesto ever written, and its message is still vital. In 1909 the Futurists refused reverence and predicted, even begged for their overthrow by the next generation: “Younger and stronger men will throw us in the wastebasket like useless manuscripts,” they cried. “We want it to happen!” Like all good manifestos, they built in their own obsolescence, clearing the way for the next vision of the future.

10. Manifestos are magic (almost).

The last century is littered with manifestos full of failed dreams and dreams that turned into nightmares, but some manifestos mark the beginning of a path to realization. Most manifestos are written from the point of view of disillusionment struggling back to hope—“hope not being hope,” as Marianne Moore’s poem “The Hero” (1932) states, “until all ground from hope has vanished.” Think of Shepard Fairey’s Hope poster for Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign: Whatever the reality, this poster’s single-word manifesto brought magic back to politics after years of disillusionment. It summed up a platform and made a promise. It energized a voting public that wanted to believe that there was something more than business as usual.

Manifestos are repositories of a kind of magic and madness that does not exist in any other genre. Take for example the Zaoum poets who were an offshoot of Russian Futurism. If the Italian Futurists were bold and brash and stylish, the Russian Futurists (who cross-pollinated with Russian Formalists like Roman Jakobson) were mad geniuses and magicians with language. One Zaoum manifesto, “The Trumpet of the Martians” (1916) by Victor Khlebnikov, announces as if in the voice of a character from science fiction: “People of Earth, hear this!”

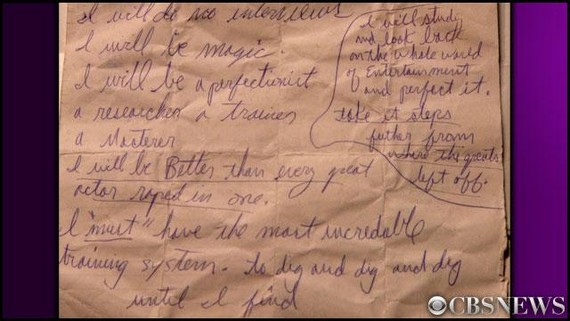

Michael Jackson wrote a manifesto, which 60 Minutes discovered and aired in 2013. In 1979 MJ laid out plans for his rebranding and subsequent world domination (“MJ will be my new name”). In its highest form, the manifesto acts as a magic spell incanted by the visionary artist. It is a performative speech/act that attempts to bring a new reality into existence. MJ’s most significant line is, “I will be magic.”

Manifesto writers over the past century have tried, above all—to paraphrase Marinetti (and Wilde)—to hurl their hopes at the stars while lying in the muddy water of modernity’s ditch.

Tone: humorous

Less words more on images

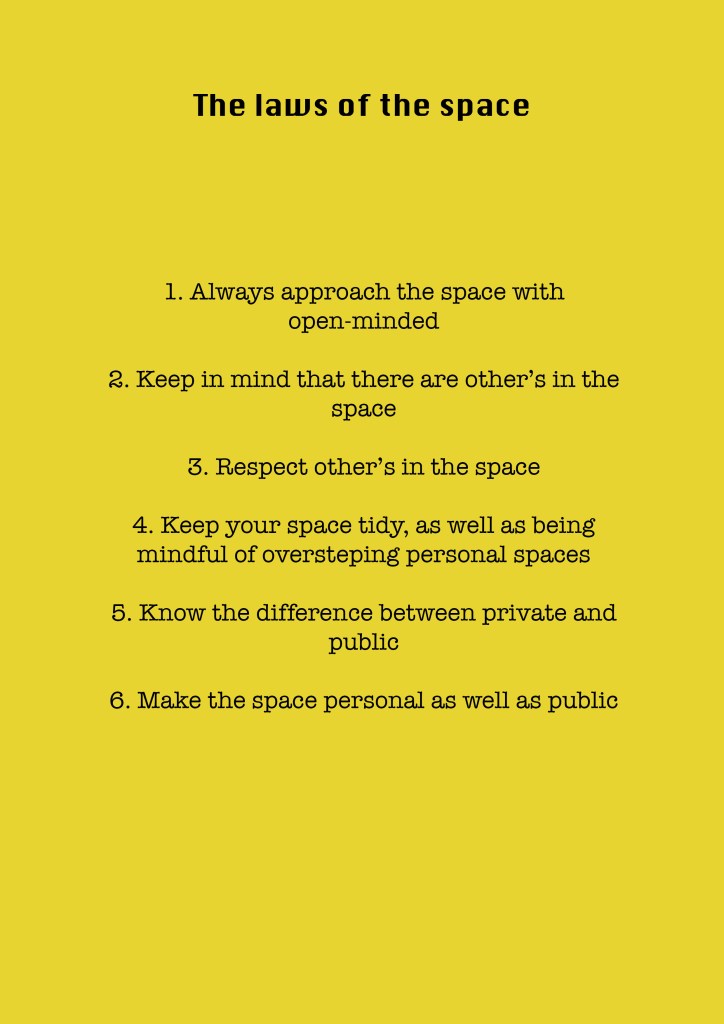

title: the laws of the space

3.

For my final design I have chosen to use the layout of listing/rules (the 3rd manifesto I have created)

Notes to put on my manifesto:

open mindedness – as you’ll be surrounded with people you don’t know therefore you don’t know what their intention to going to the site

personal bubble/space might get invaded

Rubbish laying around/ coffee stains

What I think I need to do for my manifesto development:

Clean up – too plain

Eye catching-

Refine writing

Play around with the layout

More design into the layout

Space creates :

- Attracttion

- Desire

- Distance

- Cadence

- New line

- Creativity

- Gravity

- Movement